In last week’s Labor Day post, “Celebrating Our Frontline Scapegoats,” I observed that of the seven wastes, the one most people recognize is defects. This is understandable: workers are often blamed for defect-causing situations over which they have little or no control. Today’s post continues that Labor Day theme by highlighting another way defects indirectly burden workers.

There’s a term frequently used to describe the impact of defects on workers and their machines: correction. Many people treat it as a synonym for defects, but it isn’t. Defects refer to the object of the work—for example, a product, a document, or a patient, depending on the workplace. Correction, on the other hand, is the aftereffect—sometimes long after—on workers and equipment that must deal with the defect. It’s the final insult. Correction may include rework or scrapping, or appear under euphemisms like sorting, run-in, touch-up, or troubleshooting. These activities sound like work and may even appear in the product routing, but they’re all non-value-added activities—forms of incidental work.

workplace. Correction, on the other hand, is the aftereffect—sometimes long after—on workers and equipment that must deal with the defect. It’s the final insult. Correction may include rework or scrapping, or appear under euphemisms like sorting, run-in, touch-up, or troubleshooting. These activities sound like work and may even appear in the product routing, but they’re all non-value-added activities—forms of incidental work.

Inspection is another form of incidental work related to defects. I visited a company last month where nearly every value-added operation required inspection before moving parts downstream. The mere possibility of defects drives this practice. Masquerading as proactivity, inspection is really a reaction. Shigeo Shingo argued that sampling inspection is an ineffective statistical trade-off between cost and quality. In my own factory days, before we learned to build quality into design and processing, we routinely sampled both outgoing and incoming parts between work centers. We weren’t solving problems—we were plugging holes in the dike instead of fixing it.

Even today, most organizations are just plugging the leaks, ignoring the incidental work—the waste in work’s clothing: processing waste. As Dr. Shingo described it:

“Processing itself often includes waste. Unnecessary motion, waiting, inspection, and even over-processing can be hidden in what appears to be value-added work.”

Shingo was describing a broad range of incidental work—including correction, inspection, and other hidden wastes—that are embedded in the work itself.

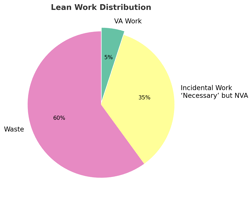

Over-processing, today the common term to describe processing waste, is just one part of this larger problem. Why does this broader definition of processing waste matter? Because when we limit our search only to over-processing (e.g., polishing a cannonball before firing), we also deem incidental work ‘necessary’ and thereby miss some of the most significant drags on human productivity.

In more than thirty years of joining customers on waste walks, I’ve seen this peculiar pattern repeatedly: defects are the most commonly identified waste, while processing waste is the least recognized.

As Shingo warned:

“The most dangerous kind of waste is the waste we do not recognize.”

Are you watching carefully for processing waste in all its forms? Please share a thought.

O.L.D.